–

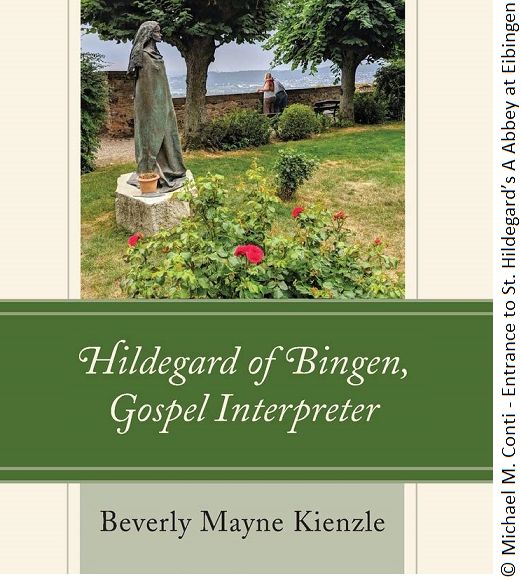

Texte original de Beverly Mayne Kienzle – Présentation de son livre “Hildegard of Bingen: Gospel Interpreter”.

.

In “Hildegard of Bingen: Gospel Interpreter” (December 2020), Beverly Mayne Kienzle introduces the reader to Hildegard’s fifty-eight Homilies on the Gospels―a dazzling summa of her theology and the culmination of her visionary insight and scriptural knowledge.

Part one probes how a twelfth-century woman became the only known female Gospel interpreter of the Middle Ages. It includes an examination of Hildegard’s epistemology―how she received her basic theological education and how she extended her knowledge through divine revelations and intellectual exchange with her monastic network.

Part two expounds on several of Hildegard’s homilies, elucidating the theological brilliance that emanates from the creative exegesis she shapes to develop profound, interweaving themes. Hildegard eschewed the linear, repetitive explanations of her predecessors and created an organically coherent body of thought, rich with interconnected spiritual symbols.

Part three deals with the wide-ranging reception of Hildegard’s works and her influence on theology, music, medicine, science, and spirituality.

.

Hildegard’s prophetic voice resounds today in the morally urgent areas of creation theology and the corruption of church and political leadership. She decries human disregard for the earth and lust for power.

Instead, she advocates the unifying capacity of nature, “viridity”, that fosters the interconnectedness of all creation. She saw all living things and all knowledge as divinely interconnected, affirming that “all creation comes from God and God is in all creation”.

This expansive theology of Creation inspires contemporary advocates for constructing a theology, that honors all creatures of the earth and moves humankind to save the environment.

.

The theology of Creation underlies Hildegard’s attacks on dualistic heresy, particularly the idea that Satan created the material world. Hildegard of Bingen: Gospel Interpreter elucidates Hildegard’s comprehensive thought and exegesis on Creation in the Homilies.

Three sets of homilies with three texts each (Homilies 34–36, 43–45, 46–48) elucidate how Hildegard masterfully develops her complex Trinitarian theology through the interpretation of gospel texts.

Especially noteworthy for readers today is Hildegard’s concept of the renewing and life-giving power of the Holy Spirit, as manifest in the rich, polyvalent image of water: the waters at Creation (Gen. 1:2), the sacramental water of baptism, and the tears of compunction.

Viridity, the life-giving power of the Holy Spirit, offers hope, refreshment, and faith in the vitality of God’s creation even when human neglect and evil destroy life around us.

While climate change worsens natural disasters such as fires, earthquakes, floods, and storms, we find inspiration to value and restore the earth as well as hope in Hildegard’s teaching that the viridity of creation will generate new growth.

.

.

Beverly Mayne Kienzle retired in 2015 as the John H. Morison Professor of the Practice in Latin and Romance Languages at Harvard Divinity School.

A past President of the International Medieval Sermon Studies Society (1996–2002), she is currently an affiliate of the Harvard Standing Committee on Medieval Studies.

Her works on Hildegard include:

The Solutions to 38 Questions of Hildegard of Bingen, co-translated (Liturgical Publications, 2014);

A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen, co-edited (Brill, 2013);

The Gospel Homilies of Hildegard of Bingen, English translation and Introduction (Liturgical Press, 2011);

Hildegard of Bingen and her Gospel Homilies: Speaking New Mysteries (Brepols, 2009);

Expositiones evangeliorum, co-edited (Brepols, 2007).

.

.

Dans “Hildegard of Bingen: Gospel Interpreter” (décembre 2020), Beverly Mayne Kienzle présente au lecteur les cinquante-huit homélies de Hildegarde sur les Évangiles – un résumé éblouissant de sa théologie et le point culminant de sa perspicacité visionnaire et de ses connaissances des écritures.

La première partie s’interroge sur la façon dont une femme du XIIe siècle a pu devenir la seule interprète féminine de l’Évangile connue du Moyen Âge. Elle propose une étude de l’épistémologie de Hildegarde – comment elle a reçu sa formation théologique de base et comment elle a élargi ses connaissances à travers des révélations divines et des échanges intellectuels avec son réseau monastique.

La deuxième partie expose plusieurs des homélies de Hildegarde, expliquant l’éclat théologique qui émane de l’exégèse créatrice qu’elle façonne pour développer des thèmes profonds et imbriqués. Hildegarde a évité les explications linéaires et répétitives de ses prédécesseurs et a créé un corpus de pensée organiquement cohérent, riche en symboles spirituels entre eux liés.

La troisième partie traite de la large réception des œuvres de Hildegarde et de son influence sur la théologie, la musique, la médecine, la science et la spiritualité.

.

La voix prophétique de Hildegarde résonne aujourd’hui dans les domaines moralement sensibles de la théologie de la création et de la corruption de l’Eglise et des dirigeants politiques. Elle dénonce le mépris des humains pour la terre et leur soif de pouvoir.

Elle préconise la capacité unificatrice de la nature, la “viridité”, qui favorise l’interconnexion de toute création. Elle considère tous les êtres vivants et toutes les connaissances comme divinement interconnectés, affirmant que “toute création vient de Dieu et Dieu est dans toute création”.

Cette vaste théologie de la création inspire les défenseurs contemporains de la construction d’une théologie qui honore toutes les créatures de la terre et incite l’humanité à sauver l’environnement.

.

La théologie de la Création étaye les attaques de Hildegarde contre l’hérésie dualiste, en particulier l’idée que Satan a créé le monde matériel. “Hildegard of Bingen: Gospel Interpreter” élucide la pensée globale et l’exégèse d’Hildegarde sur la Création dans les Homélies.

Trois séries d’homélies de trois textes chacune (Homélies 34–36, 43–45, 46–48) expliquent comment Hildegarde développe magistralement sa théologie Trinitaire complexe à travers l’interprétation des textes de l’Évangile.

Pour les lecteurs d’aujourd’hui, il est particulièrement intéressant de noter les conceptions de Hildegarde sur la puissance rénovatrice et vivifiante de l’Esprit Saint, telle qu’elle se manifeste dans l’image riche et polyvalente de l’eau : les eaux de la Création (Gen. 1:2), l’eau sacramentelle du baptême et les larmes de la compassion.

La viridité, la puissance vitale du Saint-Esprit, offre espoir, ressourcement et foi en la vitalité de la création de Dieu, même lorsque la négligence humaine et le mal détruisent la vie autour de nous.

Alors que le changement climatique aggrave les catastrophes naturelles telles que les incendies, les tremblements de terre, les inondations et les tempêtes, on peut trouver une inspiration pour valoriser et régénérer la terre, ainsi qu’une forme d’espoir, dans l’enseignement de Hildegarde que la viridité de la création engendrera un renouveau.

.

Beverly Mayne Kienzle a pris sa retraite en 2015 en tant que professeur “John H. Morison Professor of the Practice in Latin and Romance Languages at Harvard Divinity School”.

Ancienne présidente de l’International Medieval Sermon Studies Society (1996–2002), elle est actuellement membre du comité permanent de Harvard sur les études médiévales.

Ses travaux sur Hildegarde incluent:

“The Solutions to 38 Questions of Hildegard of Bingen”, co-traduit (Liturgical Publications, 2014);

“A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen”, co-edité (Brill, 2013);

“The Gospel Homilies of Hildegard of Bingen, English translation and Introduction“ (Liturgical Press, 2011);

“Hildegard of Bingen and her Gospel Homilies: Speaking New Mysteries” (Brepols, 2009);

“Expositiones evangeliorum, co-édité” (Brepols, 2007).